Fusarium head blight

FHB disease cycle. Photos by Melissa Keller. Source.

The frequently humid growing season in the Mid-Atlantic makes an infection by Fusarium fungus on grain crops almost inevitable, but if you’re prepared, it doesn’t have to ruin your harvest.

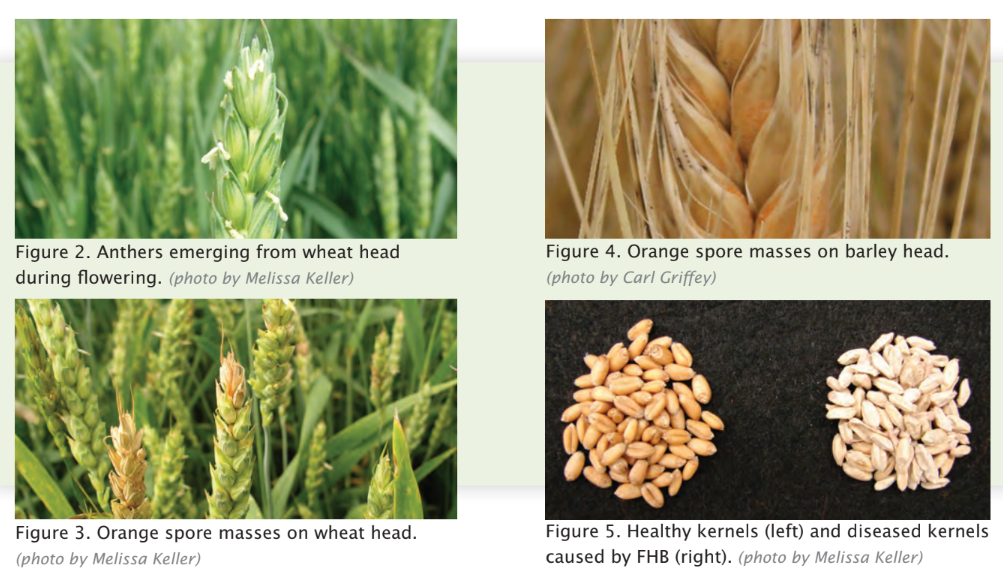

You’ll know if a plot has become stricken with Fusarium head blight (FHB), commonly known as scab, if you spot premature whitening or bleaching on heads. The greatest potential for spread occurs when anthers are exposed during flowering, but it’s possible for infection to occur later. Pink or orange spores may be visible on at least one-third or one-half of each affected head, and bleached areas may contain shriveled, discolored, and sterile kernels. On barley, infected heads could also appear brown and water-soaked.

Fusarium infection spotted on wheat and barley crops by researchers at the Virginia Cooperative Extension. Source.

A significant means of Fusarium spread, year after year, is crop residues left on the soil surface after harvest. This is visible as small, blue-black spore containers, known as perithecia, found dotting the organic matter left behind. For all the benefits of no-till or reduced till field preparation, particularly for soil health, it increases the risk that Fusarium will overwinter in the field. When average temperatures reach 75 to 85 degrees Fahrenheit with high humidity and frequent rainfall, an FHB epidemic is all but guaranteed.

Keeping an eye on potential Fusarium infection is important because it results in the development of deoxynivalenol, also referred to as DON or vomitoxin, which, logically, is a type of mycotoxin that can induce vomiting in non-ruminant animals. If testing shows high levels of DON in a grain crop, you may be offered lower than standard pricing or even have the grain refused at elevators or mills. The FDA has established an upper limit of 1 ppm of DON for grain intended for human consumption, with looser restrictions for grain intended for some animal feed.

So what are your options for managing this risk?

Use FHB resistant cultivars: While there are no varieties of wheat or barley completely resistant to FHB, there are some, such as Nueast, that are specifically developed for the disease challenges presented by the conditions on the East Coast.

Clean your harvest: Sorting out diseased grains can help achieve a better grading for your crop.

Blend it with better wheats: A local miller might be able to take your grain and combine it with a crop from another farm to reduce the overall DON measurement in the resulting flour.

Sell it as feed: If all else fails, you can still make a sale of grain impacted by FHB as animal feed, as long as DON levels are measured at no more than 10 ppm.

If you’re hoping to grow food-grade grain in the Mid-Atlantic, make sure planning for FHB is considered in your crop plan.

What has been your experience dealing with Fusarium Head Blight? Do you use any additional strategies to ensure the success of your crop and the useability of your harvest?

Heather Coiner contributed to the background research and development of this post.

This material is based upon work that is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 2019-38640-29878 through the Southern Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program under subaward number LS20-327. USDA is an equal opportunity employer and service provider. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.